Shocked Into Sobriety

Abstract: One man’s experience with substance abuse and how quitting saved his life, but not before almost killing him.

Tachycardia is broadly defined as any heartbeat above roughly 100 beats per minute. Sing “Sweet Home Alabama” in your head and drum along. That’s 100 BPM. On December 18, 2017, my heart wasn’t dancing to “Sweet Home Alabama.” At 285 BPM, my heart was tap dancing at ludicrous speed. You don’t have to be a doctor to know that’s not good. It was then that my heart was struck with a short, sharp shock that saved my life and launched a journey toward sobriety.

A SHORT, SHARP SHOCK

If you aren’t familiar with the reference you’re not alone. It will only likely ring a bell with fans of Gilbert & Sullivan or theater nerds (the Venn-Diagram is nearly a circle). It’s part of a tongue twister about a looming execution in Act 1, of Mikado.

To sit in solemn silence in a dull, dark dock,

In a pestilential prison, with a life-long lock

Awaiting the sensation of a short, sharp shock,

From a cheap and chippy chopper on a big black block.

The shock that may have meted a capital sentence at the behest of the Emperor of Japan in the above passage delivered me from one. It yanked me from the dull, dark, dock. It knocked free that life-long lock and sprung me from the pestilential prison that I had been living in for a decade.

As I screamed myself awake with the help of three thousand volts, I knew I almost surely would have died that day had several things happened differently. And I would be dead today if I had not at least attempted to get sober.

THE FIRST STEP

We admitted we were powerless over alcohol — that our lives had become unmanageable.

That’s the first step of Alcoholics Anonymous. I had long known that I was powerless over alcohol, but never saw a degree of unmanageability. I was excelling in my field. I had a long-term relationship, a mortgage, and a dog. On paper, I was managing quite nicely. But I was killing myself. With Christmas approaching, and my nephews coming into town I had a moment of clarity. I resolved to be sober for them, for the holidays.

Not knowing what I know now about the science of chemical dependency I believed ‘just stopping’ was possible and, more importantly, safe. While mentally, I wasn’t yet able to admit the unmanageability of my drinking, my body was.

WHEN QUITTING KILLS

What the Budweiser frogs or the Beefeater yeoman of the guard won’t tell you is that ethanol is one of the few substances that, when used abusively and for a prolonged period, can kill you if you stop. Heroin withdrawal will make you wish you were dead, but legal, socially acceptable alcohol will make it so.

When you’ve used alcohol, a depressant, long enough, your body changes how it functions. It constantly produces stimulant neurochemicals in an effort to break even. When the external supply of depressants ceases, the body is like a cruise ship — it takes time to stop and change course. It continues to produce these stimulating chemicals even with nothing to counteract them, causing hallucinations and severe tremors, known as Delirium Tremens, as well as seizures and death.

IT WAS TOO LATE

On that December morning, it had been roughly 36 hours since my last drink. The air was crisp but mild, and the sun sat low in the sky. At 9:26 AM, while driving alone, my mother in a car behind me, I began to feel wrong. My vision blurred; my thoughts slurred. As I drove in and out of the long, narrow shadows cast by nude trees along the two-lane road, the strobing light assaulted my senses. I started to pull over but it was too late.

Seizing before I could put my car in park, my mom had to use her car to bring mine to a complete stop. Then she had to watch through my locked door as I flopped and thrashed, blood trickling from my mouth due to a badly bitten tongue.

I’m told eventually I regained enough motor function to unlock the doors. I’m told neighbors rushed from nearby houses to help. I’m told first responders got there quickly.

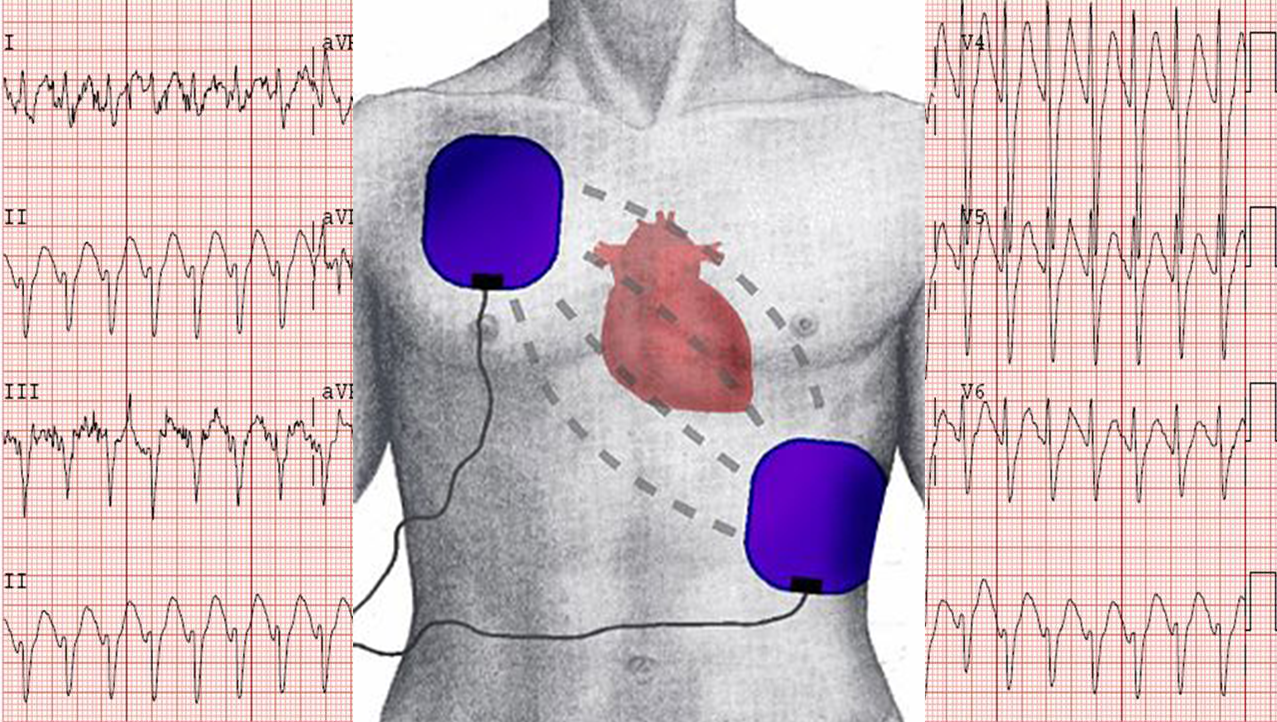

But my next memory was when I sat up in the back of the ambulance, my favorite tee shirt hastily cut off of my admittedly doughy chest, and saw two EMTs — one holding defibrillator paddles, the other an empty syringe of lorazepam.

WELCOME BACK

I felt the tingling remnants of being therapeutically electrocuted as well as the residue of a scream issuing forth from my mouth. I tasted blood. My brain struggled to catch up with what was happening. My eyes began to look beyond the two men in blue jumpsuits holding the implements that had brought me back from oblivion.

That’s when I saw my mom’s twisted, horrified face watching from the asphalt just outside. From that moment forward, the joy of drinking would never be the same. Then again, there had been no joy to my drinking for some time. While it had felt necessary for survival, it had almost meant my expiration.

AN ALLERGY TO ALCOHOL

I don’t know why I survived the grand mal seizure that sent my heart into overdrive when many others don’t. Whether due to provenance or dumb luck, I made it. Technically the defibrillator saved my life, but so did the seizure itself. Had I not received such a clear and irrefutable signal from the universe, my body, and medical professionals, I may never have been able to accept that my life was unmanageable.

Instead, without even knowing it, I had taken the first step before we even arrived at the hospital where I would spend the next four days detoxing. In triage, I was asked, “Any Allergies?” I responded, “Sulfa drugs, Penicillin, and I guess, Alcohol.”

This isn’t the origin story of a man, shocked back into consciousness, never to drink again. It’s the turning point in a story about an utterly imperfect man, who just wanted to feel at home in his own mind. It’s the beginning of a journey where sobriety came slowly, with terrific difficulty, and sometimes not at all. Yet, in that moment, that shock, I knew my life had been saved, and I would spend the rest of my life seeking a daily reprieve from that pestilential prison on that dull dark dock where I almost stayed that day.