The Soundtrack Of Censorship

overview

In the age of police accountability, activists have two valuable tools: camera phones and the internet. But despite the right to record police being codified in many parts of the country, police are beginning to push back using a novel tactic: playing copyright-protected material as a means preventing the spread of video content. It’s a creative tactic, but it’s one that raises questions about censorship and improper behavior on the part of agents of the state.

Listen to What Censorship Sounds Like

Enjoy a playlist of some of the tracks used by police to trigger DMCA takedowns.

Introduction

Background

Following the murder of George Floyd and the summer of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, police officers found themselves in a new era of public scrutiny. Not only was the nation’s attention focused on police tactics, but the role of video, filmed and disseminated by the public, played a central role in that increased scrutiny. The attention itself isn’t necessarily new — the use of force by police officers, especially against black citizens, has been a social issue that has ebbed and flowed into and out of the spotlight for over 30 years. Camera phones aren’t entirely new either.

An impromptu memorial for George Floyd in the aftermath of his murder at the hand of Minneapolis Police Officer, Derek Chauvin.

Image: USA Today.

But the way these two societal forces have combined to provide added accountability and scrutiny for police departments nationwide does seem to be a newer phenomenon. The release of Rodney King being beaten by police officers in 1991 was a pivotal cultural moment because it told a vivid story to a majority audience — a story that minority citizens knew all too well. Video told the story in a format that was indisputable. In 1991 very few people had video cameras at the ready, watching police interactions with the public. With mobile phones, any police interaction can now be readily recorded and uploaded, or even streamed live.

The increased scrutiny has not been universally welcomed by the police. With body-worn cameras becoming increasingly mandated for police, video evidence surrounding police interactions has skyrocketed on both sides— both for the police and the public. As the public has sought to record more, whether as a bystander or a subject of police interest, it has faced various forms of pushback. In some cases, officers have demanded suspects stop recording, in others, officers have deleted video recorded by a suspect or bystander after the fact.

While some federal courts have clearly held that the First Amendment covers the right of individuals to film officers, others have held that the right isn’t clearly established, especially when weighed against state wiretapping statutes and the doctrine of qualified immunity. Without Supreme Court precedent, there’s a split among circuit courts, with each Circuit of Appeals court decision determining the legality of filming police in their jurisdiction. Currently, the First, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits have all found a clearly established First Amendment right to record police. The Third, Fourth, and Tenth Circuits have all found that the right to record police is not clearly established, while the Eighth has ruled that the right has limitations. As the courts catch up with changing technology and new societal forces, some police are seeking to prevent citizen recordings, by either backing legislation placing limitations on recording police, or individual officers taking actions to limit recording, like confiscating phones.

“Copyright Hacking”

The tactic at issue in this exploration is less obvious, and potentially more legally complicated than an officer confiscating a phone or insisting a bystander delete a video. It involves officers using YouTube and other video sharing sites’ built-in copyright protection methods as a means of preventing the dissemination of videos recorded of them. It’s a novel way of using copyright law as a shield. Here’s how it works: when officers are being recorded but don’t want the recording to be shared online, they pull out their phones and play copyright-protected music. That way, if it is uploaded onto YouTube or similar platforms, if it isn’t automatically flagged by the platform it can quickly be reported as containing rights-protected content. Should this tactic be considered a method of preventing the publication of speech with which the police disagree? By playing specific content as a means of poisoning the recording, they are using copyright protections to prevent speech the officer or department doesn’t agree with, from being published? Weaponizing copyright laws is a novel new tactic, also referred to as “copyright silencing” or “copyright hacking." Individuals could, of course, post the video without audio, but the audio is often where the context and information lie.

The concept of “copyright hacking”, or playing copyrighted material to prevent dissemination, was theorized in 2019 as a potential foil to neo-Nazi rallies. By playing loud music during rallies of hate groups one could stop the spread of hate rhetoric online. Even then, the potential dangers were apparent:

The thing is, as much as it's a cute way to sabotage Nazis' attempts to spread their messages, there is nothing about this that prevents it from being used against anyone. Are you a cop who's removed his bodycam before wading into a protest with your nightstick? Just play some loud copyrighted music from your cruiser and you'll make all the videos of the beatings you dole out un-postable.

Legal Context

Filming Police

In the Fall, 2015 Texas A&M Law Review, author Clay Calvert outlines a five-step reasoning supporting the protection of recording police, under the First Amendment:

First, the Supreme Court has long held that images and films, not merely spoken and written words, are protected by the First Amendment.

Second, and more recently, the nation’s high court concluded that the act of creating such images—not merely the finished product—also is safeguarded by that amendment.

Third, courts are clear that a person generally does not possess a reasonable expectation of privacy when he or she is situated in a public place, such as a street or sidewalk.

Fourth, and in accord with the first three points, the Supreme Court has observed that public streets and sidewalks—places where police often carry out their work—“are areas that have historically been open to the public for speech activities.”

Fifth and finally, the conduct of police, as government officials, is a matter of public concern, and speech regarding matters of public concern is, as the Supreme Court recently reiterated in Snyder v. Phelps, at the heart of the First Amendment.

While this is a much more detailed chain of logic than laypeople likely go through when considering whether they are, in fact, allowed to record police activities, it outlines the foundation of that belief — recording video is a form of free speech, and police are public figures, performing public functions, in public.

A bystander films the police during protests in Ferguson, Missouri following the killing of Michael Brown at the hands of police officer Darren Wilson in 2014.

Image: CampaignZero

Yet the courts haven’t necessarily come to the same conclusion. The First, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits have all held that the First Amendment right to record police is clearly established, while the Third, Fourth, and Tenth do not recognize that right and the Eighth Circuit has ruled that the right to record police has limitations. As discussed by Brittany Mercer in the Summer, 2017 American Journal of Trial Advocacy, “Since the 1990s, a split has developed on the issue of whether the First Amendment protects a citizen’s right to record the police. Moreover, courts have struggled to balance citizens’ First Amendment rights with state wiretapping statutes, resulting in several cases lacking meaningful analysis of the law for other courts to consider.”

As noted above, state wiretapping statutes can potentially counter the public’s perceived right to record police, like in the case of Anthony Graber. A Maryland motorcyclist, Graber recorded a contentious interaction with a State Trooper during a traffic stop, via a helmet-mounted camera. Graber did not specifically set out to record the interaction, as the camera recorded most of his ride — well before, during, and after the stop. Feeling that the trooper’s behavior was heavy-handed and unreasonably aggressive, Graber uploaded the helmet cam footage to YouTube. Graber was arrested for violating Maryland’s wiretapping laws, which require two-party consent for recording any communication between multiple parties. Ultimately, the charges against Graber were dismissed, but this case demonstrates how wiretapping can potentially become a complicating factor.

The Seventh Circuit encountered a similar issue with state statutes in ACLU v. Alvarez, as the ACLU sought to bar enforcement of Illinois’ eavesdropping statute as part of a “police accountability program”. Ultimately, the court found that since the eavesdropping statute criminalized the audio recording of police, it necessitated heightened scrutiny, and the government could not meet the required burden.

The Fourth Circuit also faced a similar situation to the Graber case, in Kelly v. Borough of Carlisle, where Brian Kelly, a passenger in a traffic stop, recorded the interaction, leading to the officer conducting the stop to arrest Kelly. While the charges pertaining to the wiretapping statute were dropped, Kelly filed suit against the officer and the Borough of Carlisle for violating his First Amendment right to record the police. It is in defense of the actions pertaining to the wiretapping statute that the doctrine of qualified immunity (explored in-depth, below) was successfully invoked in this case, leading to the decision that the right to record the police was not clearly established.

Another example, from the Fourth Circuit, is the case of Szymecki v. Houck. The Fourth Circuit “rejected the notion that the right to record the police is clearly established in the circuit” and instead found that there might be a right to record.

Qualified Immunity

Qualified immunity (as outlined in Harlow v. Fitzgerald) protects law enforcement officers from liability as long as their conduct does not violate a “clearly established statutory or constitutional right of which a reasonable person would have known.” That means, if the plaintiff doesn’t make the case that a right is clearly established, judges can “make a ruling on summary judgment and end the case.”

In circuits where qualified immunity has not been successfully invoked, decisions often hinge on the precedent of Pearson v. Callahan, where the U.S. Supreme Court held that courts can use their discretion in choosing the order of analysis when faced with a qualified immunity claim. This discretion superseded a previous precedent whereby a two-step framework for determining qualified immunity claims was outlined in Saucier v. Katz. That two-step framework was first to “determine whether the constitutional right had been violated. If so, courts were then required to… determine whether the constitutional right at the time was clearly established enough to place a reasonable officer on notice.” Under Pearson, courts could then rule on either step first.

The role of qualified immunity has precipitated the split among circuits, as it forces the question of whether or not the right to record the police is “clearly established”. There does seem to be a trend toward holding that the right is, in fact, clearly established or at least should be, as the Fifth Circuit found in Turner v. Lieutenant Driver. “Although the right was not clearly established at the time of Turner's activities, whether such a right exists and is protected by the First Amendment presents a separate and distinct question […] We conclude that First Amendment principles, controlling authority, and persuasive precedent demonstrate that a First Amendment right to record the police does exist, subject only to reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions.” While the Fifth Circuit didn’t hold that the right was clearly established at the time, it affirmed the right to record police is covered under the First amendment.

THE DMCA

Originally enacted in 1998, the Digital Millenium Copyright Act, or DMCA, was designed to streamline and modernize copyright enforcement. The DMCA’s proponents argued that copyright was safer “if the copyright claimant could, with the click of a mouse, remove allegedly infringing content.” Ultimately, the DMCA provides protections to rights holders and platforms or internet service providers.

Historically, copyright law established two boundaries, as in Abrams v. United States: limiting the scope of rights to specific expressions, not underlying ideas, and protecting fair use in cases of limited, transformative purposes, including commentary, criticism, or parody. What Section 512 of the DMCA introduced is a process by which a claimant (typically the rights holder) need only claim “a good-faith belief that the target is infringing” upon protected copyrights. Platforms and providers then provide a means for taking down infringing content and are thereby protected from copyright claims, themselves. The “takedown” is meant to provide a 10-to-14 day assessment period, during which the takedown can be appealed. The platform that receives the takedown request has no way of assessing whether a claim is in “good faith.” Due to secondary copyright liability, there is a disincentive for platforms to scrutinize requests — especially when requests are made by major record labels and movie studios. As a result, platforms will grant the vast majority of DMCA takedown requests automatically, and the 10-to-14 day evaluation period, which has brought the DMCA takedown before courts.

In Lenz v. Universal Music Publishing Inc., the Ninth Circuit found that copyright holders have a “duty to consider – in good faith and prior to sending a takedown notification – whether allegedly infringing material constitutes fair use.” Again, this relies on the “good faith” actions of the accuser.

An additional complication is how DMCA takedowns are becoming increasingly automatic and algorithm-driven. While automatic takedowns are more efficient and don’t rely on a human being poring over thousands of websites’ content, algorithms lack accountability. They provide little room for fair use, nor do they include the very human concept of “good faith” on the part of the takedown request or consideration of the “good faith” of the user that posted the content. Automated enforcement is explored further in the next section.

Additional issues

Automated enforcement

A key element complicating the potential for copyright abuse is that most platforms rely on some degree of automated systems to implement DMCA takedowns of copyrighted material. One of the most prominent systems is Content ID, the automated system employed by YouTube. How it works is YouTube allows rights holders to register a piece of video or audio content. Any upload is checked against these specifically registered pieces of content, looking for matches. It is not restricted to pure copy-and-paste uses of content — audio could be in the background, or video content could appear on a screen within the recording. Once Content ID identifies a piece of protected content, the rights holder has discretion about what action is taken next. The video could be blocked outright (a traditional DMCA takedown), an advertisement could be added to the piece of content, with the proceeds going to the original rights holder, or the rights holder could instead opt to simply track the viewership of the content. Regardless of the actions taken, the offending uploader would receive a notice of Content ID violation, details of what restorative action is being taken, and directions for appeal. But, in the case of appeals, the restorative action remains in place until the appeal is successful. Most platforms follow a similar protocol with minor idiosyncrasies. For example, Instagram has the option for video content with protected audio to remain active, but with muted audio.

Of course, DMCA takedowns can be initiated outside of automated systems, but it’s these automated systems that are increasingly responsible for the heavy lifting. While this provides convenience and control for platforms and rights holders alike, it offers very little room for interpretation of fair-use cases. It also lacks the understanding of the “good faith” of the poster and the required “good faith” of the takedown. Even outside of the case of police misconduct at hand, automated systems can have unintended consequences.

One case that earned some attention was a day-long conference for the Canadian Citizens Climate Lobby. The event was live-streamed to YouTube, and shortly after lunch, the entire video link (starting at the very beginning of the day) was muted. The reason was that the live stream captured audio of the DJ playing copyrighted music during the lunch break. Since the conference was set up for a pure live stream, no video was recorded locally, so the entire record of the day was rendered essentially useless by muting the entire 7-hour video. As a remedy, the video was made private which allowed for the retention of the audio and video record of the day, but the ability to share the goings-on of the conference publically was seemingly irreparably neutered by the incidental inclusion of copyrighted material. This is a prime example of how automated takedowns don’t take into account whether infringing content could ever be injurious to the rights holder. No music fan will ever tune into this conference for a poor-quality, overheard, pop-music playlist that is background music for a climate conference lunch break. It also represents an absence of “good faith” accounting — most humans with any sense would recognize that the incidental inclusion of copyrighted material was just that, incidental.

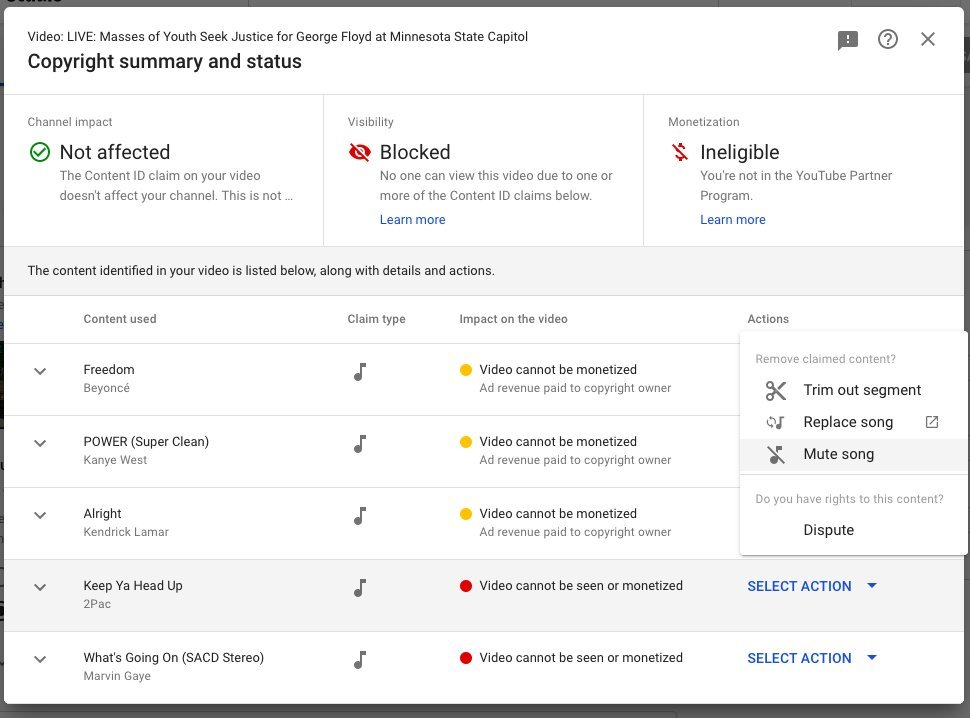

A screenshot of the takedown notice, received by the user who posted video and interviews from the youth rally at the Minnesota State Capital.

Image: Twitter User @UR_Ninja

Another example, a little bit closer to the matter at hand, was a youth rally at the Minnesota State Capitol building in 2020. A content producer and activist recorded the event and conducted several interviews with protesters. Shortly after the video was uploaded to YouTube and Facebook, the user received a takedown notice due to the music being played in the background. The protester was given the option of muting the copyrighted sections, but doing so would mute the interviews rendering the video useless. The users believed they were being censored by the tech platforms for their political stances when it was likely more a consequence of the automated takedown system of the respective platforms. But due to their outrage, it garnered a modicum of attention on tech websites and social media, which is the only way we really know about it. Millions of takedowns happen every day, mostly automated, and if the user is unsuccessful in appealing and doesn’t have a platform to complain about it, the takedown remains in place without any outward evidence it ever happened.

Copyright as a weapon

John Tehranian boldly states in the November 2015 Iowa Law Review that “Copyright law has become the weapon par excellence of the 21st-century censor. Fueled by a desire to prevent one’s perceived foes from making certain types of speech, an individual has no better friend.” Specifically, the aspect of copyright law most often invoked by the aforementioned “21st-century censor” is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (or DCMA) which is previously described. As discussed in both the DMCA and Automated Enforcement section, the DMCA is meant to take into account “good faith” actors — both on the part of the alleged infringer and the rights holder.

But what if the accuser isn’t acting in good faith? In an example outlined by Tehranian, it’s conceivable that a service provider, such as a doctor, could include a provision in the patient-intake agreement that grants the doctor copyrights to any reviews a patient may write about services provided. Then, if there were ever a review with which the doctor disagreed, he/she as the copyright holder could issue a DMCA takedown claim.

In a study of DMCA takedowns, “notices involving uncopyrightable subject matter and fair use represented 30% of the takedown notices studied.” Another study within the same work suggests that “57% of the takedown notices to Google are from companies demanding the takedown of material posted by competitors” suggesting that DMCA provisions are seen as a weapon to combat speech with which the petitioner disagrees or wants to disrupt, instead of purely as a means of protecting content to which the petitioner possesses copyrights.

Another reason takedowns can be weaponized is DMCA takedowns and copyright laws do not consider harm. Legal scholar Christina Bohannan points out that “Although the First Amendment sometimes protects even harmful speech, it does not allow the prohibition of harmless speech. The one glaring exception is copyright law.” The role of copyright law is intended to protect the rights holder from harm inflicted by unauthorized use of intellectual property, encouraging “the creation and dissemination of expressive works.” However, “courts frequently impose liability without proof that the defendant’s use of copyrighted material caused any harm that could realistically affect those incentives.” Bohannan suggests that a better standard for viewing harm in copyright disputes could best be described as “the harm must be of such a nature and to such an extent that it would be expected to reduce the copyright holder’s ex-ante incentives to create or distribute her copyrighted works.” Ideally, legislation could be crafted in such a way that using a harm-based approach can serve as a bulwark against abuses in copyright cases.

Intent

Intent is tricky. As a matter of law, intent plays a critical role in prosecuting a crime, and entire works of scholarship are dedicated to the subject. While this exploration doesn’t deal directly with intent as a legal concept, intent is an important filter through which individual incidents can be viewed. In some cases, intent is clear: the officers involved explicitly state that they are playing copyright-protected material to prevent the video from being disseminated online. But in the cases where the officers play dumb, act coy, or are completely non-communicative, there are some inferences that we can make based on musical choices.

Ignoring the legal context around playing copyright-protected material, what are some potential reasons officers might play music during an interaction with a member of the public? One reason could be to drown out any conversation. A claim could even be made, however specious, that drowning out communications between officers would be a matter of operational security. If that were the case, you wouldn’t expect the sparse and dulcet tones of The Beatles’ “Yesterday” to be used. Instead, loud and complex dubstep or even white noise would be more effective.

Another conceivable, albeit farfetched, rationale might be a matter of psychological warfare. After all, the US Military notoriously blared rock and metal music at the compound of Manuel Noriega in 1989 for three days, as “Music Torture” in an effort to coax the Panamanian strongman out of his compound. A similar tactic was used against Branch Davidians during the Waco standoff in 1993 and against the Taliban during the war in Afghanistan. If this were the motivating factor for playing music through patrol car PA systems in a residential neighborhood, you might expect music closer to the US Military’s 1989 playlist, instead of Disney hits.

So what can the musical choices tell us about the intent? Disney, The Beatles, and Taylor Swift have one thing in common aside from being hit factories: they’re notoriously protective of their copyright and litigious. Disney is probably the best known for going to great lengths to protect its copyrights. In 1989, Disney threatened to sue three small daycare centers for murals that included Disney characters. More recently, an elementary school in California had a movie night where they screened The Lion King for a PTA fundraiser. The school was contacted by Disney and charged a $250 licensing fee — prompting outrage and an eventual apology from Disney CEO, Bob Iger.

The Beatles have a similar track record of copyright protections, suing over 50-year-old concert footage and a messy dispute with Apple Computers over the “Apple” name and trademark. And Taylor Swift engaged in a bitter batter of wills with the company that owned the masters for her catalog, as well as a dispute with Spotify over what she felt was unfair compensation for her work.

So what might this say about the officers’ intent? One could infer that by playing the works of protective rights holders, the police officers are trying to use music that is most likely to be subject to stringent takedowns.

How Widespread Is This?

It’s difficult to say. Due to the way takedowns can potentially shut down video content, the most notable incidents available come from activists who have a platform to raise awareness when they encounter the tactic. If a takedown is successful against an individual with a small social following we have no way of hearing about it. Even if the tactic is used unsuccessfully, without a following or a platform to draw attention to the attempt, the incident remains within that individual’s small network.

Geographically, “copyright hacking” is likely to only be used in states covered by the circuits that have positively affirmed a clear right to record police, since in other states officers have other, easier, and more direct ways to prevent filming. That leaves the First, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuit states as potential locations to find this tactic.

It’s also impossible to know how frequently the tactic’s use has stopped bystanders from recording or caused them to decide not to post. The examples that we do have are mostly due to activists knowing their rights and using their platform to raise awareness. In these cases, police officers end up feeling The Streisand effect — a phenomenon of the internet age whereby trying to block attention about a subject draws more attention to the subject.

Incidents

Sgt. Fair vs Fairness Part 1

The first recorded instances of this police tactic come from Beverly Hills, CA, ironically involving an officer named Fair. Between January and February 2021, there are at least 3 instances of Beverly Hills Police Department playing copyrighted material while being recorded.

Context:

Location: Beverly Hills, CA

Date: January 16, 2021

Filmed By: @mrcheckpoint_ & @alwaysfilmthepolice, Sennett Devermont

Copyrighted Material: “Yesterday”, The Beatles

An activist and credentialed member of the press, Sennett Devermont, approached a group of Beverly Hills Police Department officers to ask some questions, and almost immediately one of the officers produced a phone and began to play “Yesterday” by The Beetles. The officer playing the music, Julian Reyes, didn’t engage directly with Devermont, but Sergeant Billy Fair pointed Devermont’s attention toward the music.

Fair, the same BHPD officer involved in a later incident, left the situation to have a conversation with someone a few yards away, but ultimately it was Fair that was the only one to engage Devermont. Fair made it clear that the music was in an effort to avoid accountability and scrutiny, saying “I just never know if I’m going to be that one bad clip” and “there’s too much pressure when you’re here”. When Devermont pointed out that Fair is wearing a body cam, drawing equivalency between the two methods of recording video (bodycam and member of the public filming), Fair said “My body camera isn’t waiting for one of us to make a mistake.” The implication, whether accurate or not, was that Devermont was there to record any mistakes that the officers may make, and the music was to avoid that.

This video was being broadcast live to Instagram, instead of recorded and later uploaded to a site like YouTube. Therefore, if Instagram were to remove the video, there would have been no local recorded copy.

Legal Environment:

Circuit: Ninth — Right to record police clearly established

Location: City Street — a public space

Legal or Institutional Consequences:

This incident, in conjunction with the other incident involving Sgt. Fair, was noted by the BHPD as “under review”, releasing a statement that “the playing of music while accepting a complaint or answering questions is not a procedure that has been recommended by Beverly Hills Police command staff”. [SOURCE]

Media Response:

Sgt. Fair vs Fairness Part 2

Now a familiar face, Sgt. Fair again attempts to prevent being captured on video by playing music in two separate encounters on the same day.

Context:

Location: Beverly Hills, CA

Date: February 5, 2021

Filmed By: @mrcheckpoint_ & @alwaysfilmthepolice, Sennett Devermont

Copyrighted Material: “Santeria”, Sublime

Less than a month after Sennett Devermont had an interaction with Beverly Hills Police Department where they played “Yesterday” by the Beatles in an attempt to thwart filming or dissemination, Devermont had a similar interaction with one of the same officers. This time, Devermont, a well-known police accountability activist with press credentials, went to the BHPD office to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. As he does whenever he interacts with police, he live-streamed the interaction, something with which the officer, Sgt. Billy Fair disagreed.

After a brief back and forth between Fair and Devermont, Fair pulled out his phone and began to play “Santeria” by Sublime. Fair did not respond to Devermont’s repeated questions about why he was playing music.

Later that same day, Devermont encountered Fair outside the department, and Fair explained his behavior, saying that he couldn’t hear Devermont through the glass. Again, he began to play music and claimed that he can’t hear Devermont. Devermont suggested he turn down the music, as Sgt. Fair covered his body camera.

Legal Environment:

Circuit: Ninth — Right to record police clearly established

Location: Public area of BHPD office, and later a city street — a public space

Posted Restrictions: Visible in the video, there is a no phones sign

Legal or Institutional Consequences:

This incident, in conjunction with the other incident involving Sgt. Fair, was noted by the BHPD as “under review”, releasing a statement that “the playing of music while accepting a complaint or answering questions is not a procedure that has been recommended by Beverly Hills Police command staff”. [SOURCE]

In the aftermath, Devermont also outlined how even though Instagram didn’t immediately remove the video, it has had a chilling effect on publishing the story. He pitched the story to a TV news network but a producer told him via email, “Heads up, the story will not post online because of the music […] Legal says we can’t play The Beatles.” [SOURCE]

In Vice reporting, Devermont privately shared a video of a third incident involving BHPD, from weeks earlier, where the officer played “In My Life” by The Beetles. [SOURCE]

Media Response:

Country Music In Rural Illinois

Not restricted to Southern California, “copyright hacking” is used in a rural Illinois community. This is also the first use that suggests there is institutional support for the tactic.

Context:

Location: Ottawa, IL

Date: Feb 25, 2021

Filmed By: “Accountability Angel”, Angel Farmer

Copyrighted Material: “Nobody But You”, Blake Shelton, feat. Gwen Stefani

An activist, Angel Farmer, who goes by the name Accountability Angel on YouTube, visited the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Office to deliver misconduct complaint forms and to request FOIA release forms. Upon arriving at the office, she was greeted by a notice on the door forbidding filming within the office, apparently a new policy. Having previously filmed when visiting the sheriff’s office, and under the impression that her right to film in the public spaces of the office was protected, Angel asked what had changed and refused to stop filming.

Ultimately, a security officer was called (later identified as James Knoblauch, a retired chief of police from a nearby town). Once Knoblauch arrived, Angel began to question him about the new rules and why she wasn’t able to carry out her business while filming and without responding, Knoblauch begins to play Blake Shelton’s “Nobody But You.”

As Angel asked questions, Knoblauch remained stoic, turning up the volume on the music while still preventing her from entering the office. Ultimately, Angel figured out what was going on, telling viewers “Oh guys, you know what they're doing, they're trying to get me kicked off of YouTube for the copyright thing.”

Legal Environment:

Circuit: Seventh — Right to record police clearly established

Location: Public area of Sheriff’s Office — a public space

Posted Restrictions: A sign that prohibits any photography

Legal or Institutional Consequences:

Immediately following the incident, Angel filed a complaint with the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Office. Through a FOIA request from Vice and Motherboard, the incident report is public record. In it, Knoblauch states “As I was recently advised, I then turned on some music”. This seems to indicate that this was a tactic encouraged by a supervisor or coworker. No public statement was issued by the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Office, nor was any investigation or action beyond the incident report taken. [SOURCE]

The local paper, the LaSalle News Tribune, included no stories about the incident and it’s not clear if the issue gained any traction locally. In the weeks following the incident Angel had a further conflict with the Sheriff’s Office, leading to a physical altercation. The altercation and eventual charges against her and her brother did make the local news, without any mention of the February 25th incident. [SOURCE]

Media Response:

Blank stares and blank spaces

Having made news in Southern California, the tactic is repeated in Northern California.

Context:

Location: Oakland, CA

Date: July, 2021

Filmed By: Anti Police-Terror Project (APTP)

Copyrighted Material: “Blank Space”, Taylor Swift

During a protest outside the pre-trial hearing of a police officer who shot Steven Taylor, an unarmed black man, activists had a disagreement with an Alameda Sheriff Deputy over the placement of a banner. As activists tried to film the interaction, the deputy, Sgt. David Shelby pulled out his phone and played Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space”.

The intentions of the deputy were clear as the deputy explicitly said in the video that he was playing the music to prevent dissemination of the video on YouTube. “You can record all you want, I just know it can’t be posted to YouTube”, remarked the deputy. Later, he’s even more explicit: “I’m playing music so that you can’t post on YouTube.” As the interaction progressed, he tried to backtrack, by saying that he was just listening to music.

Legal Environment:

Circuit: Ninth — Right to record police clearly established

Location: Courthouse Steps — a public space

Legal Or Institutional Consequences:

Within the video, the deputy was asked whether playing music to prevent dissemination is part of the department’s procedure and the deputy responded “It’s not specifically outlined.” In the aftermath of the video receiving broad attention from media outlets, the sheriff’s department said through a spokesperson, “We have seen the video and referred it to our internal affairs bureau. This is not approved behavior. It will not happen again”. [SOURCE]

The department spokesperson also referenced law enforcement’s responsibility, “Obviously in our world, we have an oath to uphold the First Amendment, not to trigger censorship of the First Amendment. And that’s what this is about. He’s aware he made a terrible mistake. We’re human. He was trying to play a game with the activists, and it went wrong. I can tell you this, too. It doesn’t work. If you try to censor video on YouTube or social media, it’s only going to make that video go viral.” When pressed about the potential consequences, the spokesperson added “Is this a termination-type case? No, it is not. Is this a reprimand or something enforced administratively, we’ll have to wait to see.” [SOURCE]

Later, department officials said they had “addressed the incident” with the deputy, a 15-year veteran, and had instructed all deputies about appropriate procedures. An investigation was launched into whether the deputy violated the department’s code of conduct and the sherrif’s office also put in place a policy that specifically prohibited such behavior. [SOURCE]

Media Response:

Disney after dark

“Copyright Hacking” remains an issue in Southern California. The most recent case proved to be a perfect storm of public attention, involving an entire neighborhood, including a City Councilman, awakened by loud copyrighted material blasted by police.

Context:

Location: Santa Ana, CA

Date: April 4, 2022

Filmed By: Santa Ana Audits

Copyrighted Material: “You’ve Got A Friend In Me”, Randy Newman, “We Don’t Talk About Bruno”, Encanto, and other Disney-owned songs

In the late hours of April 4th, a YouTuber who posts videos under the account Santa Ana Audits started filming Santa Ana police officers on a public street investigating a car theft. The police officers responded by using the PA system of one of their vehicles to loudly play Disney music. Among the songs played were “You’ve Got A Friend In Me” from Toy Story, and “We Don’t Talk About Bruno”, from Disney’s recent hit movie, Encanto.

As the street is residential, several residents were awakened by the loud music and came out to investigate (in addition to the YouTuber filming). Unfortunately for the officers, one of the residents disturbed by the music was Santa Ana City Councilman, Jonathan Ryan Hernandez.

When pressed as to why they were blaring the music loudly, the officer tells the councilman that the YouTuber was interfering with their investigation and the music was played so that the man filming “will get copyright infringement”.

Legal Environment:

Circuit: Ninth — Right to record police clearly established

Location: A public road

Legal or Institutional Consequences:

Obviously, since this incident directly involved a City Councilman, it received immediate attention from the city government. Before even getting to the copyright issue, there was the fact that the officers were blasting music in a residential area, in the middle of the night (a weekday night, no less). Had it been a private citizen doing so, they undoubtedly would have earned a visit from the police, and likely would have received a citation for a noise violation or disturbing the peace. Adding in the intent behind the music — to discourage filming and dissemination — only makes the issue worse.

It’s not even clear in the video if there was any contentious interaction with a suspect underway. From the video, it appears that the officers were just investigating an empty car. With that in mind, it’s not necessarily what the YouTuber was recording with which the officers took issue, it’s more that there was someone filming at all.

At an April 19th City Council meeting, the broader City Council members condemned the officers’ behavior and directed the City Manager to implement an official policy that codifies the right of the public to film the police. Councilman David Penaloza said, “That was one of the most embarrassing things I’ve ever seen.” [SOURCE]

The City Manager, Kristine Ridge confirmed that the playing of music was “completely outside” official policy. She further outlined the litmus test for the varying levels of accountability that the incident required, “It’s a violation currently (of a noise ordinance,) so the investigation that’s ongoing will determine, did that officer violate policy? If so, he will be held accountable. Did he violate the Municipal code? If so, it will be referred to the city attorney. Did he violate a criminal code? If so, it will be referred to the D.A.” [SOURCE]

Santa Ana Police Chief, David Valentin released a statement that read “The Santa Ana police department is aware of a video that has surfaced involving one of our officers. We are committed to serving our community and we understand the concerns as it relates to the video. The Santa Ana police department takes seriously all complaints regarding the service provided by the department and the conduct of its employees. Our department is committed to conducting complete, thorough, and objective investigations. My expectation is that all police department employees perform their duties with dignity and respect in the community we are hired to serve.” [SOURCE]

Mayor Vicente Sarmiento weighed in when he agreed that the larger issue is the effort to prevent the dissemination of video of the officers doing their job, especially in a situation where it didn’t seem like there was any potentially sensitive activity going on. The police simply seemed to take issue with being filmed while doing their job. The mayor further supported the right to record as an important part of police accountability, referencing both Rodney King and George Floyd. Finally, the mayor added “What bothers me most about this practice is that we’re trying to build trust with the community […] We’re trying to establish this relationship where we say, ‘When you see something, say something.’ Well, sometimes, all you can say is to videotape something or to document something. And this really chills that sort of activity.” [SOURCE]

In response to the incident in Santa Ana, when combined with the stories from Beverly Hills and Oakland, nearby Burbank issued an order to all uniformed officers explicitly prohibiting them from engaging in similar conduct. [SOURCE]